Extinction is a powerful reminder of the delicate balance of our ecosystem and how easily it can be disrupted. You might think most animals go extinct due to overhunting or habitat loss, but the reasons can sometimes be unexpected and downright strange. In this listicle, you’ll discover 14 animals that met their end for reasons that might leave you scratching your head. As you read on, you’ll find that human impact, in one form or another, often plays a part, even if indirectly. So, let’s dive into the peculiar stories of these lost species.

1. Great Auk

The Great Auk was a large, flightless bird native to the North Atlantic. Unlike the dodo, which was famously hunted for food, the Great Auk was targeted for its down feathers. In the 1500s, hunters sought these birds to meet the demands for warm bedding, which was all the rage in Europe. This excessive hunting continued until the 19th century, when the Great Auk’s populations had dwindled dangerously low. According to researcher Jeremy Gaskell, the last confirmed sighting was in 1844, highlighting the relentless human pursuit that led to this bird’s extinction.

In addition to hunting, the Great Auk faced habitat challenges that compounded their decline. These birds primarily nested on remote islands, which were gradually disturbed by human activities. The introduction of rats, dogs, and other predators by sailors also contributed to their downfall. Even as numbers dwindled, collectors sought the remaining Auks for museum specimens. It was a tragic combination of exploitation and habitat disruption that sealed their fate.

2. Tasmanian Tiger

The Tasmanian Tiger, also known as the thylacine, was a carnivorous marsupial native to Tasmania. Despite its name, it wasn’t a tiger but got its nickname from its striped back. Human settlers believed the thylacine posed a threat to livestock, which led to them being hunted extensively. The government even offered bounties to incentivize their eradication, a decision that drove the species closer to extinction. By the early 20th century, the last known Tasmanian Tiger died in captivity.

Unfortunately, hunting wasn’t the only issue this species faced. Habitat destruction further reduced their numbers, as human expansion encroached on their natural environment. Diseases introduced by domestic dogs also played a role in their decline. Despite sporadic claims of sightings, no conclusive evidence has emerged to prove their continued existence. The Tasmanian Tiger remains a poignant example of how fear and misunderstanding can lead to irreversible loss.

3. Passenger Pigeon

Passenger pigeons once swarmed North American skies in flocks so large they could darken the sky for hours. However, this abundance didn’t prevent their downfall. The 19th century brought large-scale hunting for meat, which was considered an affordable protein source for many Americans. As the hunting intensified, the pigeons’ social nature, which relied heavily on large communal nesting, became a disadvantage. Researcher Joel Greenberg highlights that by the early 20th century, these birds were unable to find the critical mass needed for successful reproduction.

This extinction story is as much about habitat loss as it is about hunting. Deforestation for agriculture has reduced their natural habitats significantly, making it difficult for them to find food and nesting sites. As forests shrank, the competition for resources increased, forcing the pigeons into smaller and smaller areas. By 1914, the last known passenger pigeon died in captivity at the Cincinnati Zoo. It’s a testament to how quickly abundance can turn to scarcity through human intervention.

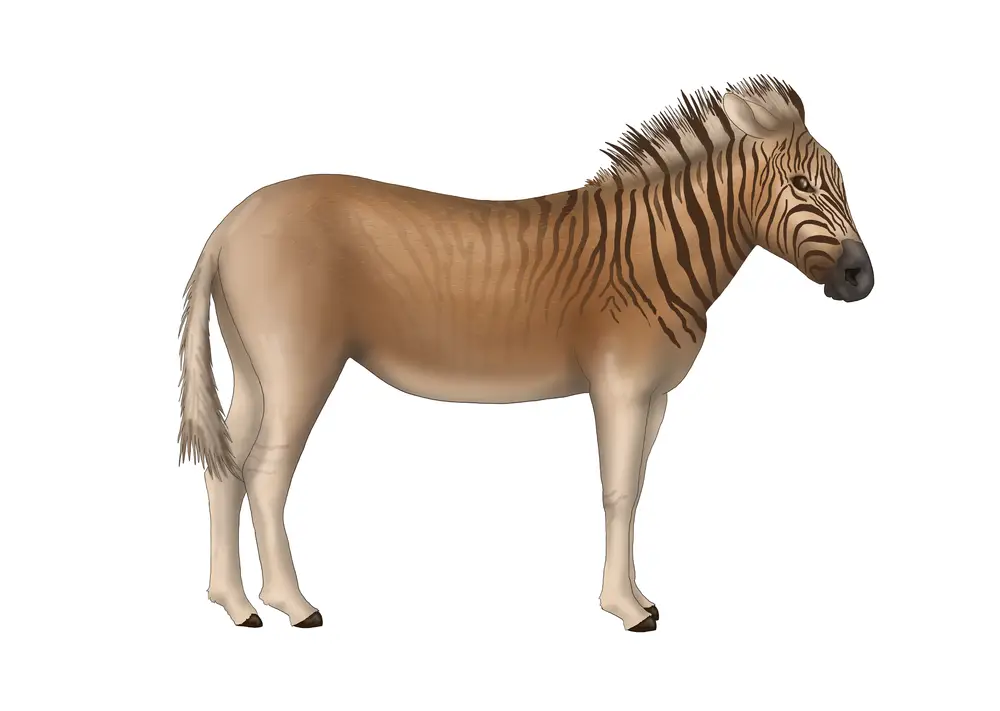

4. Quagga

The quagga was a unique subspecies of the plains zebra, distinguished by its half-striped, half-brown coat. Native to South Africa, these creatures were extensively hunted by European settlers for their hides and to clear land for farming. This overhunting led to a rapid decline in their population during the 19th century. Unlike other zebras, the quagga’s distinct appearance made it a sought-after target, accelerating its extinction. The last known quagga died in an Amsterdam zoo in 1883.

In addition to hunting, the quagga faced competition for resources with the livestock introduced by settlers. Their natural grazing lands were converted to pastures for cattle and sheep, squeezing out native species. As domesticated animals increased, pressure on the local ecosystem grew, leaving less for the quagga to survive on. Conservation efforts were nonexistent at the time, and awareness came too late to make a difference. This story underlines the broader environmental changes that occur with colonial expansions.

5. Steller’s Sea Cow

The Steller’s sea cow was a massive marine mammal discovered in the Arctic waters of the Bering Sea in 1741. It was a relative of the manatee and dugong, but much larger, weighing up to 11 tons. Unfortunately, this gentle giant was hunted to extinction within 30 years of its discovery. Hunters targeted the sea cow for its meat, hide, and fat, which were highly prized by Russian and European explorers. According to marine biologist James Swann, the unregulated hunting practices of the time showed complete disregard for the species’ survival.

The demise of the Steller’s sea cow was not solely due to direct hunting. The species also suffered from habitat changes caused by human activity, such as the hunting of sea otters, their ecosystem partners. Sea otters kept sea urchin populations in check, which in turn protected the kelp forests that the sea cows fed on. As sea otter numbers fell, the balance was disrupted, leading to the degradation of vital feeding grounds. Thus, the extinction of the Steller’s sea cow was a tragic case of unintended ecological consequences.

6. Golden Toad

The golden toad was a small, brightly colored amphibian native to the cloud forests of Costa Rica. Known for its vivid orange hue, this toad species was discovered in 1966 but vanished just a few decades later. The dramatic population decline was primarily due to climate change, which altered their habitat significantly. Increased temperatures and changes in rainfall patterns disrupted their breeding cycles, making it harder for them to survive. By 1989, no more golden toads were observed, marking their extinction.

In addition to climate change, the golden toad faced pressure from an increasing human population nearby. Urban development led to deforestation, which further fragmented their already limited habitat. This fragmentation left the toads more susceptible to diseases, such as the chytrid fungus, which is deadly to amphibians. Conservation efforts were too late to save this charismatic creature. The extinction of the golden toad serves as a stark warning of how quickly environmental changes can erase a species.

7. Pyrenean Ibex

The Pyrenean ibex was a subspecies of the Spanish ibex that lived in the Pyrenees Mountains. It was a beautiful, sturdy animal known for its impressive horns and ability to navigate rugged terrain. Unfortunately, hunting in the 19th and early 20th centuries drastically reduced their numbers. By the time protective measures were put in place, the population was too small to recover. Biologist Alberto Fernández-García noted that disease and genetic factors further compounded their struggle for survival.

Efforts to conserve the Pyrenean ibex included a controversial attempt at cloning, which initially seemed promising. In 2009, scientists successfully cloned an ibex using preserved skin samples. However, the clone only survived for a short time, dying shortly after birth due to lung defects. This endeavor marked the first de-extinction, although it was ultimately unsuccessful. The Pyrenean ibex remains an icon of the challenges and possibilities in conservation science.

8. Moa

The moa were flightless birds native to New Zealand, ranging in size from small turkeys to towering giants. They were once plentiful and played a crucial role in their ecosystem as browsers and grazers. However, the arrival of Polynesian settlers around 1300 AD marked the beginning of their decline. Moas were extensively hunted for food, and their eggs were collected, leading to a rapid population decrease. Within 100 years of human arrival, these unique birds were extinct.

In addition to hunting, habitat destruction hastened the moas’ demise. The settlers cleared vast areas of land for agriculture, which removed the forests that moas depended on for food and shelter. Invasive species introduced by humans also posed threats, as they competed with or preyed upon native species. Without any natural predators before human arrival, moas were ill-equipped to deal with these new challenges. Their extinction serves as a powerful example of the swift impact human colonization can have on wildlife.

9. Haast’s Eagle

Haast’s eagle was the largest eagle to have ever existed, native to the South Island of New Zealand. It preyed primarily on the moa, which provided ample sustenance for its massive size. However, as the moa population declined due to human hunting, so did the food source for Haast’s eagle. Unable to adapt quickly enough to these changes, Haast’s eagle vanished shortly after its primary prey. This extinction was an indirect consequence of human impact on another species.

The disappearance of Haast’s eagle highlights the interconnectedness within ecosystems. With the loss of its main prey, the eagle faced starvation, leading to its rapid decline. Habitat changes caused by forest clearing also affected the eagle, which relied on large tracts of wilderness for hunting. The introduction of new predators and competitors further strained the eagle’s existence. This story underscores the ripple effect that the extinction of one species can have on others.

10. Caribbean Monk Seal

The Caribbean monk seal was a marine mammal once abundant in warm Caribbean waters. These seals were easy targets for hunters due to their approachable nature and the fact that they rested on beaches. They were hunted for their oil, which was valuable in the 18th and 19th centuries. Over time, the combination of hunting and habitat disturbance from human activities led to their decline. The last confirmed sighting of a Caribbean monk seal was in 1952.

In addition to hunting, the species faced challenges from increased human presence in their habitat. Fishing activities depleted their food sources, making it harder for them to survive. Pollution and coastal development further degraded their environment, leading to a decline in suitable resting and breeding areas. Conservation efforts were minimal, as the plight of the monk seal went largely unnoticed until it was too late. Their extinction is a sad reminder of how easily a species can slip away without adequate protection measures.

11. Baiji Dolphin

The Baiji dolphin, also known as the Yangtze River dolphin, was a freshwater dolphin native to China’s Yangtze River. It was often called the “Goddess of the Yangtze” and was revered in Chinese culture. However, industrialization and development along the river took a heavy toll on these dolphins. Pollution, ship traffic, and habitat loss due to dam construction led to a severe population decline. By 2006, an extensive search failed to find any remaining individuals, leading to the declaration of its extinction.

The Baiji’s extinction was a direct result of human activity disrupting their natural environment. Water pollution from industrial waste and agricultural runoff made the river increasingly inhospitable. Noise pollution from boat engines interfered with their echolocation, crucial for navigation and hunting. The construction of dams disrupted the natural flow of the river, affecting the availability of food and suitable living conditions. This case exemplifies the dire consequences of unchecked industrial growth on riverine species.

12. Pinta Island Tortoise

The Pinta Island tortoise was a subspecies of giant tortoise native to the Galápagos Islands. It gained fame with the discovery of Lonesome George, the last known individual of his kind. Human activity on the islands, including hunting and habitat destruction, drastically reduced their numbers. Introduced species like goats destroyed much of the vegetation that the tortoises relied on. Despite conservation efforts, no other Pinta Island tortoises were found before George’s death in 2012.

The extinction of this tortoise highlights the challenges of preserving biodiversity on islands. Islands are especially vulnerable to changes, as species there often have limited ranges and specialized niches. The impact of introduced species can be devastating, as they compete for resources and alter the ecosystem. Efforts to eradicate goats and restore habitats came too late for the Pinta Island tortoise. Its extinction is a reminder of the importance of proactive conservation measures to protect vulnerable island species.

13. Western Black Rhinoceros

The Western black rhinoceros was a subspecies of the black rhino once found in several African countries. Heavy poaching for their horns, fueled by demand in traditional medicine, led to their decline. Despite protective measures, enforcement was weak, allowing illegal hunting to continue unabated. By the start of the 21st century, sightings had become exceedingly rare, and in 2011, they were declared extinct. This tragic story is a stark reminder of the devastating impact of the illegal wildlife trade.

Poaching wasn’t the only threat to the Western black rhinoceros. Habitat loss due to agriculture and human settlements further squeezed the rhinos into smaller areas. Political instability in some range countries also hindered conservation efforts, making it difficult to protect remaining individuals. Despite international awareness and conservation programs, efforts were too fragmented and inconsistent to be effective. The extinction of the Western black rhinoceros underscores the urgent need for coordinated global action to combat wildlife crime.

14. Japanese Sea Lion

The Japanese sea lion was once common in the coastal waters around Japan. They were hunted for their oil, which was used in lamps, and their skin, which was made into leather goods. Overhunting in the early 20th century led to a rapid decline in their population. The sea lions were also victims of bycatch in fishing operations, further reducing their numbers. The last known sightings were in the 1950s, and they were declared extinct in the 1970s.

The loss of the Japanese sea lion highlights the cumulative effects of human exploitation. In addition to hunting, changes in their marine environment due to industrial pollution played a role. Coastal development also encroached on their natural habitats, leaving them fewer places to rest and breed. Despite awareness of their plight, little was done to protect them before it was too late. Their extinction is a stark reminder of the need for sustainable practices to ensure that marine life can thrive.