So, here’s a fun existential crisis for your Monday: Earth is basically doing donuts around the Sun in a cosmic demolition derby, and there are giant space rocks out there that might crash the party. You’d think we’d have asteroid threats under control by now (hello, we’ve got streaming services on our phones), but nope—some of these bad boys are still playing interplanetary peekaboo with our orbit. And scientists? Oh, they’re watching. Like, refreshing-their-radar-data-every-hour watching.

While most of these rocky rascals are just doing harmless fly-bys, a handful have earned their spot on Earth’s official “oh no” list. Whether it’s their size, speed, weird spin, or just suspiciously close passes, these are the asteroids giving astronomers anxiety sweats and inspiring actual planetary defense missions. No tinfoil hats needed—just a healthy respect for space chaos and a few solid backup plans. Let’s take a tour of the 12 asteroids that are getting the side-eye from space agencies across the globe. Spoiler alert: Some of them are way too close for comfort.

1. Bennu

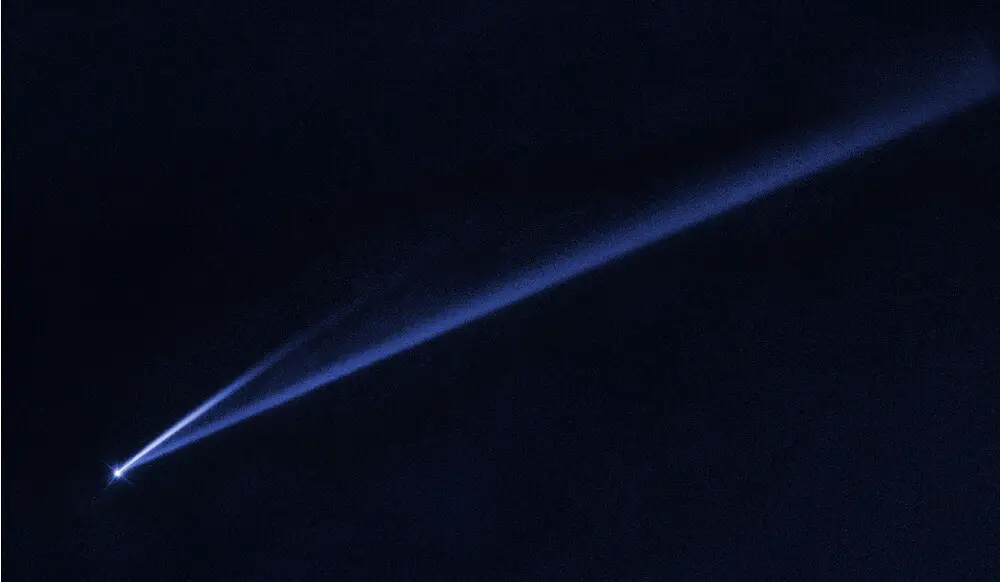

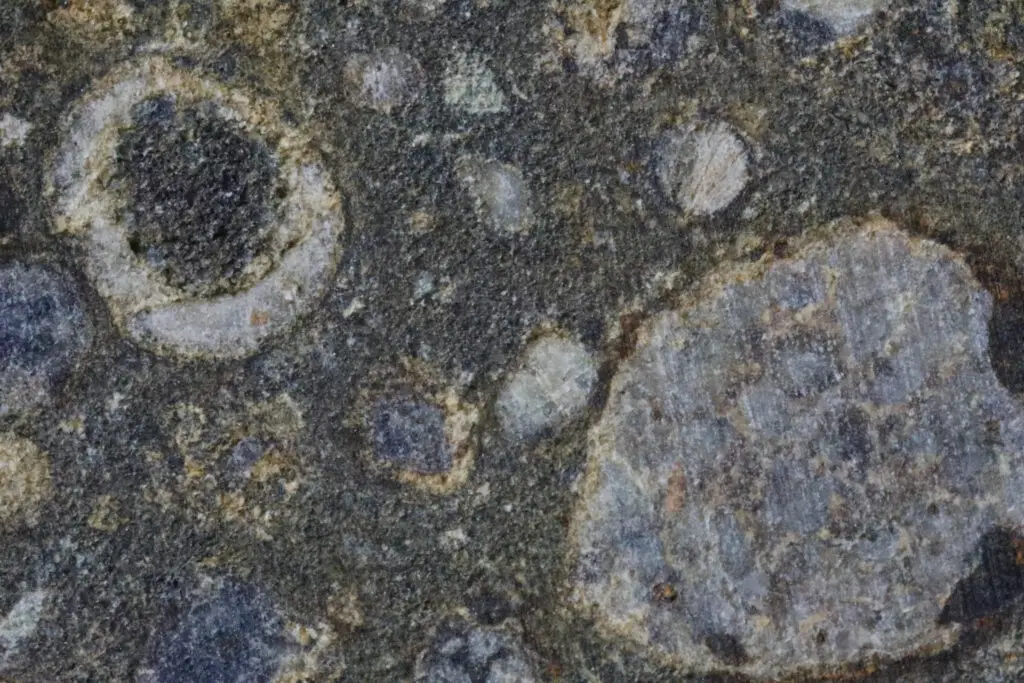

Bennu is basically the Hollywood blockbuster of asteroids: a half-kilometer wide carbonaceous behemoth with a 1 in 2,700 chance of smacking Earth in September 2182—enough to inject hundreds of millions of tons of dust into our atmosphere and trigger a decades-long “impact winter.” According to Reuters, a collision could drop global temperatures by 4 °C, cut rainfall by 15 %, and deplete the ozone layer by a third, while unleashing firestorms and shockwaves across continents. Scientists got this intel thanks to OSIRIS-REx’s laser-precise tracking, which honed Bennu’s orbit and Yarkovsky-effect estimates, slashing impact uncertainties yet still keeping us on edge. Bennu loops by Earth every six years, and while its immediate risk is officially “tiny,” its second-highest Palermo Scale ranking keeps mission planners busy refining deflection strategies. NASA’s OSIRIS-REx even snagged a sample from Bennu in 2023—because if you’re going to worry about something, you might as well poke it with a robotic arm.

Bennu’s gravity field is so weak that a hefty fist bump from the spacecraft could send surface pebbles sailing into space, making remote sample acquisition a high-wire act. Analysis of those samples is already reshaping our ideas of how organic molecules formed in the early Solar System—talk about mixed feelings when your asteroid might help explain life’s origins while also threatening to wipe it out. Plus, Bennu’s spin-driven “mole-hill” topography and unpredictable surface boulders are a navigational nightmare, forcing engineers to rethink touchdown protocols. Between its size, composition, and wobbling trajectory, Bennu is the poster child for why we can never, ever let our cosmic guard down.

2. Apophis

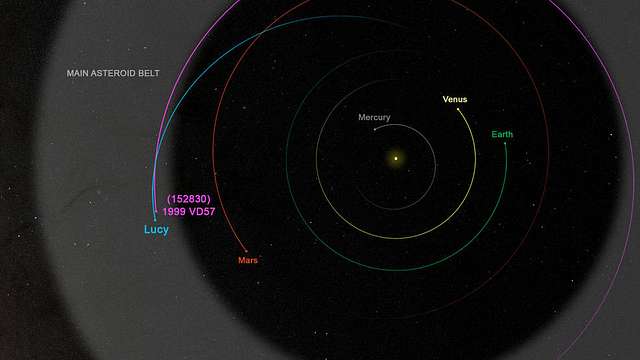

Sure, Hollywood’s chosen Apophis as a supervillain name, but the real 99942 Apophis isn’t here for theatrics—it’s a 340-meter Apollo-group asteroid that snagged global headlines when initial orbit models gave it a 2.7 % chance of impact in 2029. As reported by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, those odds have since plummeted to zero for the next century, yet its record-breaking close approach on April 13, 2029, will whisk Apophis within 31,600 km—inside the ring of geosynchronous satellites. That’s a space traffic jam waiting to happen, and scientists are itching to use radar imaging and spectroscopy to nail down its interior structure and spin dynamics.

The hype around Apophis prompted ESA and NASA to simulate deflection scenarios—complete with gravitational tractors and kinetic impacts—so if future observations hint at a shift, we’re ready. Plus, OSIRIS-APEX plans to rendezvous with Apophis in 2029 for an 18-month “surface-pepper-spray” experiment, studying how thruster burns reveal subsurface materials. It’s a shopper’s preview of planetary defense tech—call it DIY home renovation, asteroid edition. With its unusually low inclination and frequent Earth fly-bys before 2029, Apophis remains a high-value target for telescopes worldwide.

3. 29075 (1950 DA)

This one’s a name only a risk-management team could love: 29075 (1950 DA) is a 1.3-km Apollo-group asteroid that once held the record for the highest Palermo Scale rating (0.17) due to a 1 in 306 chance of impact in 2880. Per Space.com, subsequent observations and thermal-model refinements in 2015 cut that probability to 1 in 8,300—and today it sits at roughly 1 in 2,600, with a Palermo rating below zero. Despite being centuries away, the size of 1950 DA (equivalent to 75 billion tons of TNT) means any future collision would be a civilization-shaker, so astronomers keep tightening its orbital arc with radar and optical data, hoping to drive impact odds down to pure background noise.

Because 1950 DA spins retrograde, its Yarkovsky drift could nudge it closer or farther over centuries, making long-term forecasts dauntingly complex. NASA and ESA coordinate observations whenever it’s in range, while students track its ephemeris for “global-stats” science fair projects. And even if 2880 feels like sci-fi, this asteroid reminds us that planetary defense takes generational persistence—like saving for retirement, but on a cosmic timescale.

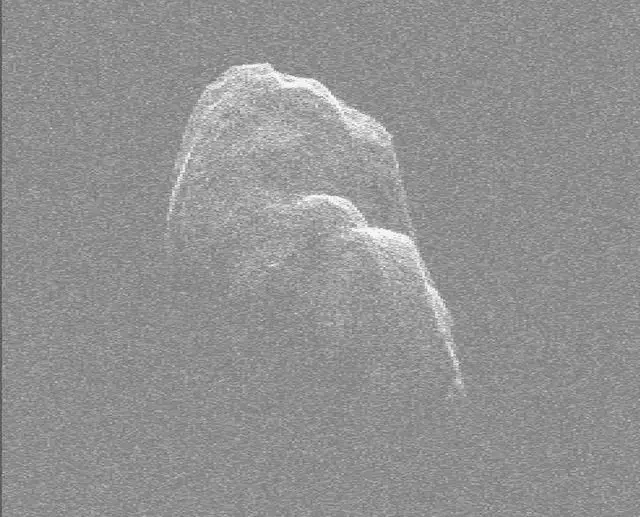

4. (52768) 1998 OR2

Clocking in at almost 2 km across, 1998 OR2 is one of the biggest “harmless” fly-by monsters, swooping to within 6.3 million km of Earth on April 29, 2020—still a safe 16 lunar distances away. As noted by UCF Today, its 0.0087 AU MOID (Minimum Orbit Intersection Distance) keeps it in the PHA (Potentially Hazardous Asteroid) club, even though its Torino Scale is firmly at zero. Scientists use radar imaging during each approach to map its cratered surface and spin state, feeding the data into impact models just in case.

OR2’s elongated 3.68-year orbit swings it from just outside Venus’s path to the main belt, and its 0.57 eccentricity makes for wild velocity shifts—20 km/s at perihelion, down to 17 km/s at aphelion. It’s like catching a bullet train on a roller coaster. With an absolute magnitude of 15.8 and a well-constrained observation arc, OR2 is probably safe for the next few thousand years—but hey, check back in 2079 when it comes within 4.6 million km for an encore.

5. (231937) 2001 FO32

This Apollo-group speedster made headlines when it whizzed past Earth on March 21, 2021, at 2 km/s, coming within 2 million km—five times the distance to the Moon. According to the Sentry monitoring system, FO32 poses no near-term collision threat, thanks to its well-defined orbit and a 0.00375 AU MOID. But at roughly 1 km in diameter, an unexpected perturbation centuries down the road could have us dusting off deflection plans.

FO32’s extreme eccentricity (0.83) means it spends most of its time beyond Mars before swinging into Earth’s neighborhood, giving astronomers rare observation windows to refine its Yarkovsky effect and spin axis orientation. Its high inclination also means it passes above or below most debris fields—still, engineers use each opportunity to test radar-tracking algorithms and laser-ranging techniques. Like a cosmic stress test, FO32 keeps our planetary defense drills sharp.

6. 2023 TL4

Discovered in late 2023, this 330-m carbonaceous asteroid briefly flirted with Torino Scale 1 before ground-based follow-ups nuked the threat. It’ll cross within 0.15 AU of Earth in 2119, but current models peg impact odds at under 0.00055 %, so it’s more of a “maybe-one-in-a-million” cartoon-villain than a true menace. Still, its recent discovery and short observation arc remind us that smaller PHAs can pop up unexpectedly, keeping surveys like NEOWISE and LSST on their toes.

2023 TL4’s tilt and composition hint at a rubble-pile interior, so if we ever needed to nudge it, kinetic impactors might just do the trick—no nukes required. Meanwhile, telescopes worldwide queue for radar slots to pin down its spin, all while mission planners debate whether to prototype a small “cubesat ram” test on it by 2050.

7. 2007 FT3

Once showing a teeny 1 in 115,000 chance of impact in 2024, 2007 FT3 turned out to be a false alarm—Toro scale 0 forever. At roughly 340 m, it’s a chunky asteroid with a 4.5-year orbit, crossing inside Earth’s path only twice a decade. Yet each rediscovery and orbit update pushes back the clouds of uncertainty, illustrating why international survey coordination is crucial—otherwise, we’d be running deflection simulations for every new object that pops up.

2007 FT3’s rotation period (5.5 hrs) and albedo (0.25) suggest a stony, monolithic core, making deflection “easier” in theory. But its moderate inclination still challenges radar visibility. It’s a perfect test case for refining asteroid-tug strategies under the Planetary Defense Coordination Office umbrella.

8. 1979 XB

A late-’70s discovery that leapt onto the radar in the early 2000s, 1979 XB measures 660 m across and crossed within 0.02 AU in 2015. Its impact odds for 2113 hover around 0.000055 %, according to NASA risk tables—effectively zero, but the centuries-out projection keeps it in the PHA database. Its slow 8 hr spin and patchy brightness variations point to a segmented interior, so any deflection mission would need high-resolution reconnaissance first.

1979 XB reminds us that historical observations (dating back decades) are golden for orbit-fitting—and that any newly found “lost” objects with old photographic plates deserve a second look. Because the longer we track them, the less wiggle room they have to surprise us.

9. 2003 MH4

A three-football-field-long rock, 2003 MH4 swoops by every 3.2 years to within 0.048 AU. NASA keeps it flagged due to its size and MOID, though its impact probability is essentially zero for the next millennium. It’s mostly a radar-mapping darling—scientists peer at its surface roughness and thermal inertia to fine-tune Yarkovsky models.

Since 2003 MH4 spent years unobserved after discovery, its orbital arc was initially shaky—teaching astronomers that follow-up within weeks is mission-critical. Now, its well-pinned trajectory makes it a reliable case study for surface-structure experiments using infrared and radar interplay.

10. 2002 NV16

Dubbed a “city killer,” this 180 m Apollo asteroid skimmed 2.8 million mi away in October 2024, prompting live radar imaging sessions worldwide. Its 4.8 yr orbit loops inside Earth’s path at each perihelion, giving rise to a MOID of 0.02 AU. Though Torino 0 today, 2002 NV16’s moderate size and mid-century close-approaches keep it in the PHA watchlist, especially as new light-curve data hint at a tumbling spin state that complicates long-term predictions.

NV16’s radar albedo suggests a metallic core, so if we ever need a deflection prototype, it might absorb kinetic hits rather than shatter—say hello to kinetic-tractor hybrid concepts. And every tiny radar jitter in its trajectory is logged and re-fed into orbital models—because in planetary defense, there are no “too small to track” objects.

11. 2015 HM1

A swift Apollo asteroid named for its discovery year, 2015 HM1 buzzed 0.04 AU from Earth in 2023. At just 150 m, it’s under the 140 m “NASA completeness” threshold, highlighting how many mid-sized PHAs still lurk undiscovered. Its Torino 0 status masks the fact that an object this size hitting a city could cause localized devastation equal to a small nuclear blast—so ground- and spaceâ€based surveys now prioritize sub-200 m objects.

2015 HM1’s spin and spectrum suggest a porous, carbonaceous composition, making optical tracking a challenge when it’s dim. Future IR telescopes like NEOCam aim to fill these blind spots—otherwise, surprises like Chelyabinsk (20 m) remind us that sudden warning times can be zero.

12. 2024 TR6

Just detected in early 2024, this 160 m asteroid skirts inside 0.03 AU every 5 years, earning it a PHA tag with a 0.00008 % Palermo rating for a potential 2051 approach. Its very recent discovery and limited observation arc mean upcoming returns are golden chances to refine its risk. Space agencies are already slating radar windows in 2029 and 2034 to pin down its Yarkovsky drift.

2024 TR6 may be small, but it’s a perfect example of why continuous sky surveys—ground-based, airborne, and space-based—are essential. After all, in the cosmic lottery, even long odds can come up, and we’d rather have a plan than panic when the numbers land.